Violence, Human Rights, and Democracy in the Philippines

Our Story

The Project

The Third World Studies Center of the University of the Philippines Diliman and the Department of Conflict and Development Studies of Ghent University started in January 2018 the research and advocacy project “Violence, Human Rights, and Democracy in the Philippines.”

This project brings together representatives from the academic community, civil society, and the media into a research network to undertake, initially, a collaborative research from January 2018 to December 2019. The overarching goal is to produce, and subsequently disseminate, rigorous research outputs that can sustain an evidence-based intervention in ongoing public debates in the Philippines about violence and tendencies towards authoritarianism.

With this project, we aim for an empirically informed analysis about the Duterte administration’s particular use of violence in its various iterations to govern the country. We seek to contribute to public debates about the state of violence in the Duterte administration and the Philippines in general. All of us are still grappling to make sense of current events and feel a need for more informed research and analysis that go beyond daily reporting and social media discussions. Amidst the polarized discussions between the opponents and the supporters of the current administration, we wish to make public research outputs that are based on hard evidence, on lived experiences, that will reinvigorate the narratives towards an effective critique of state violence. Mainly a critique of violence as abetted by the state as well as other consequent acts that revolve around the current state of violence. Importantly, this research will serve as the empirical backbone for the advocacy/outreach components of this project.

The project’s first phase “Violence, Human Rights, and Democracy in the Philippines: Strengthening the Quality and Impact of Academic Research” started last January 2018 (Year 1), and is ongoing until the end of 2019 (Year 2). Phase 1 focuses mainly on the book chapter production, and the publication of an open access book.

The steering committee was able to extend the project to 2020 for a second phase “Violence, Human Rights, and Democracy in the Philippines: Publishing and Disseminating an Open Access Book” where Phase 1’s Year 2, and Phase 2’s Year 1 overlap. Phase 2 focuses on the advocacy side of the project.

EVIDENCE-BASED RESEARCH

Doing the Research

A multisectoral undertaking to produce, and subsequently disseminate, rigorous research outputs that can sustain an evidence-based intervention in ongoing public debates in the Philippines about violence and tendencies towards authoritarianism.

GROUNDED RESEARCH

We regard grounded empirical research as the foundation for the credibility and legitimacy of our research outputs and advocacy goals. Put simply, we first want to address the question “what exactly is happening in locality x, y, or z?” before rushing into the question “why is x, y, or z happening?”

Variation Across Localities

We recognize that the underlying drivers as well as effects (including responses) of violence and human rights violations may differ across localities. And by localities we mean not only articulations on the subject of violence in a subnational level (neighborhoods, towns, provinces, regions) but even those not within a defined geography but is sustained by a vigorous network, for example political actors in cyberspace or other online communities. Elaborating on what explains variation among multiple cases might potentially constitute one of the most important innovative analytical insights to this project.

Multidisciplinary Approach

We do not favour one particular research methodology over another. Rather, we recognise that in order to adequately account for the multidimensional nature of violence, we need to adopt a multidisciplinary research approach.

Historical Awareness

We want to look beyond the here and now of the Duterte administration and adopt an analytical outlook that is attuned to potential (dis)continuities in public debates about violence, the state, and society in the Philippines.

Beyond Academe

We do not wish to confine the research component to academic researchers formally employed in universities, but also want to include civil society activists and journalists. Different groups have different capacities and skills. Moreover, including a variety of case study researchers will add to the broader dissemination of the research output.

Lines of Inquiry

The research parameters of violence, state, and democracy are selected in such a manner that they capture the larger units at work in the research milieu, whilst still allowing the individual researcher to establish a research plan according to personal interests, insights, and engagements. Broadly, we imagine the following questions to serve as jump-off points for the research plans:

- How do these views on state, violence, and democracy play out in your area, in your network within a given locality?

- If all of it hold true, or even some of it, in what ways are they true? In what ways are they not applicable?

- What alternative views are you willing to offer to explain such and such occurrences in your locality?

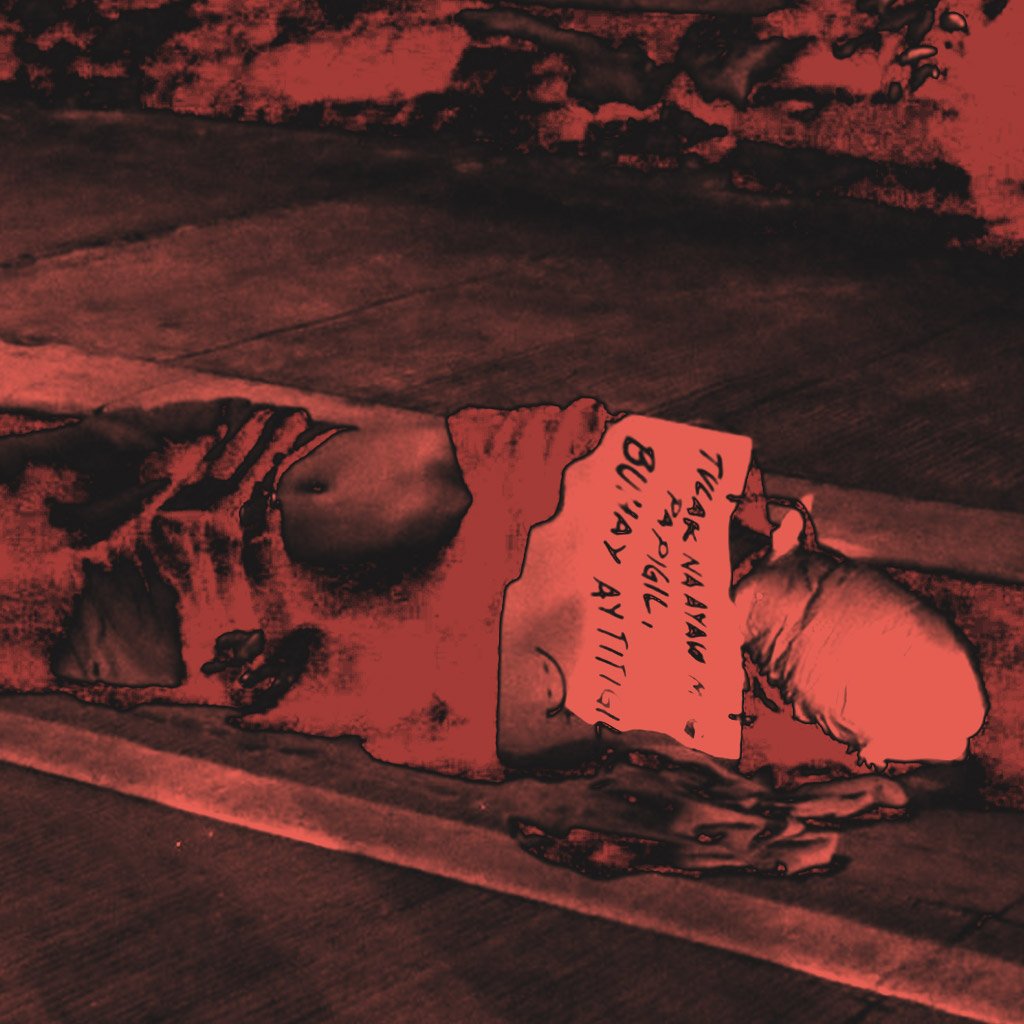

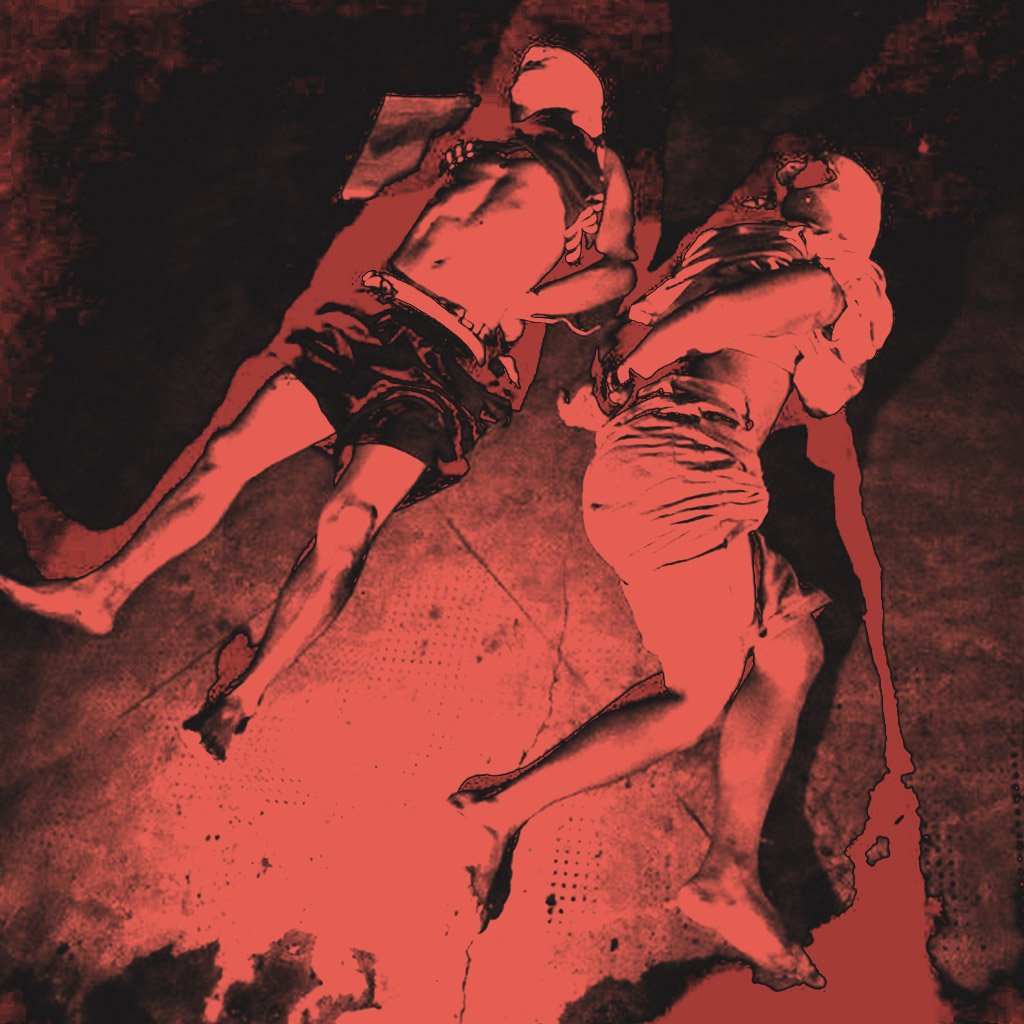

Violence

Violence constitutes the focal point of this project as it is one of the most defining discussions that erupted since the 2016 presidential elections. Violence—and the explicit call for violence—has been one of the main campaign platforms of the current administration. Moreover, the excessive use of violence through the war on drugs and extrajudicial killings has been one of the main features of the Duterte regime. Clearly, a climate of impunity, fear, and intimidation has been introduced, which not only affects different arenas of state governance, but also permeates everyday social relations. Considering the omnipresence of violence, this is a crucial research parameter to critically engage with. We are aware that what constitutes violence is subject to rich and important philosophical debate and discussion. Whilst acknowledging the complexity of the term “violence,” at this very moment however, we do not immediately wish to engage with these discussions and depart from a rather straightforward interpretation, that can always be enriched in a later stage. More specifically, within the confines of this project we wish to discuss direct physical violence against humans and the multiple threats and intimidations to inflict this physical violence. As such, research projects can be included tackling the rhetoric and performative quality of violence, discourses of violence, violence against women, threats and intimidations in cyberspace, etc.

The State

Discussion about the state seems crucial to our project. Above all, we wish to delve into a set of questions targeting the organizational infrastructure of the state as a violent actor. Put simply: who or what (administration, institution, etc.) is behind the violence? What is the relationship between the executive (at different administrative levels and institutions) and the presidential palace in the execution of violence? Considering the geographical variation among different cases, questions can also pertain to state-periphery interactions.

Clearly, debates about the nature of the Philippine state in relation to violence have a long tradition as can be gleaned from established concepts such as “bossism,” “local authoritarian enclaves,” or “cacique democracy.” Underlying many of these discussions is the claim that despite a substantial democratization after the People Power Revolution of 1986, the Philippine state has never ceased to be a prime institution of both legitimate and illegitimate violence. Furthermore, various researchers have pointed out that the local executive (municipality and barangay) in particular has maintained a considerable capacity for state-induced violence against citizens or political opponents. In other words, it seems that violence often tends to have a decentralized quality. A crucial question therefore is how this observation relates to the seemingly centralized quality of the violence inflicted by the Duterte regime. And if a democratic state brutalizes a section of its population to supposedly safeguard the well-being and interest of a vast majority, how does this impact on its legitimacy to govern?

Democracy

The occurrence of the ongoing violence and the war against drugs cannot be separated from the observation that the current administration holds a credible democratic mandate and that Duterte has been elected by 39 percent of the Philippine voters. This puts forward a whole range of questions that concern the nature, limitations, and prospects of democracy, not only in the Philippines but also across the globe. A first question concerns the meaning of this observation about the state of democracy in the Philippines and the significance as well as legacy of the post-1986 democratic turn. One must take note that Duterte’s entry into politics was ushered in by this watershed event. For the next three decades, Duterte consolidated his rule in Davao City via a political dynasty that trafficked in vigilantism and alleged illicit activities as he developed a modus vivendi with other anti-statal forces in the region. He made Davao City “progressive” as he observed the procedural trappings of an electoral democracy while strategically consolidating a network that is made common by reliance on violence and patronage to further its cause. In Duterte’s campaign for the presidency, Davao City, the locality underpinned by these undemocratic tendencies, was held up as an example of what he can accomplish. Is Duterte then the potent underside of the post-EDSA republic?

Once in office, the Duterte administration lost no time in capitalizing on its legitimate and democratic mandate to reshape the democratic institutions of the country. Most notable for its ferocity and sheer violence is the war on drugs. This campaign created a subhuman other, the drug user, whose annihilation must be achieved if the republic was to remain safe and in order. Is the targeted use of violence, extrajudicial killings, and human rights violations buttressed by this democratic mandate? If a democratic mandate can be made to justify the state’s assault on basic human rights, for how long can that state sustain its democratic credentials before becoming decidedly authoritarian? What kind of resistance and opposition will such state yield?

VLIR-OUS (Vlaamse Interuniversitaire Raad-Universitaire Ontwikkelingssamenwerking or the Flemish Interuniversity Council-University Development Cooperation) provided the funding for the research.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM

The Research Network

Steering Committee

Jeroen Adam

Department of Conflict and Development Studies, Faculty of Political and Social Sciences

Ghent University

Joel Ariate Jr.

Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy

University of the Philippines Diliman

Elinor May Cruz

Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy

University of the Philippines Diliman

Steven Schoofs

(former)

Department of Conflict and Development Studies, Faculty of Political and Social Sciences

Ghent University

Advisory Committee

Miriam Coronel-Ferrer

Department of Political Science, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy

University of the Philippines Diliman

Zosimo Lee

Department of Philosophy, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy

University of the Philippines Diliman

Frances Lo

11.11.11 Asia

Eufracio Abaya

College of Education

University of the Philippines Diliman

Luz Rimban

Konrad Adenauer Asian Center for Journalism

Ateneo De Manila University

Rosanne Rutten

Department of Anthropology, Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences

University of Amsterdam

Gert Van Hecken

Institute of Development Policy and Management

University of Antwerp

Case Study Researchers

Jose Jowel Canuday

Department of Sociology and Anthropology, School of Social Sciences

Ateneo de Manila University

Augusto Gatmaytan

Ateneo Institute of Anthropology

Ateneo de Davao University

Karol Ilagan

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism Part-time Lecturer, Department of Journalism

University of Santo Tomas

Agatha Fabricante and Christine Fabro

University of Santo Tomas

Aniceta Baltar

Concerned Citizens of Abra for Good Governance

Dianna Therese Limpin

(former)

Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy

University of the Philippines Diliman

Mary Ann Manahan

University of Antwerp

Global Greengrants Fund

Leny Ocaciones

University of San Carlos, Cebu

Raymond Palatino

Bagong Alyansang Makabayan (BAYAN) Metro Manila

Ruth Siringan

(former)

Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy

University of the Philippines Diliman

Nastashia Mikhaila Tysmans

University of Antwerp

Brian Ventura

Division of Social Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences

University of the Philippines Visayas

Maria Criselda Judy Yabes

Independent Journalist

Research Associates

Christian Victor Masangkay

(former)

Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy

University of the Philippines Diliman

Dianna Therese Limpin

(former)

Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy

University of the Philippines Diliman

Ruth Siringan

(former)

Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy

University of the Philippines Diliman

Jamaica Jian Gacoscosim

Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy

University of the Philippines Diliman

Nixcharl Noriega

Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy

University of the Philippines Diliman

Student Assistants

Kryzsa Cabeguin

University of the Philippines Diliman

Jag San Mateo

University of the Philippines Diliman

Ralph Retamal

University of the Philippines Diliman

Jewel Mae Regnim

University of the Philippines Diliman

Interns

Zachariah Williams

(former)

Cardiff University

Marianne Davies

(former)

Cardiff University